Language helps us communicate. Through it, we convey meaning – and give shape to ideas.

Language is powerful. It can build up or tear down. It can open the door or shut people out. It can emphasise our shared humanity or deepen the divisions between ‘us’ and ‘them’.

Sometimes, a certain style of language is so deeply ingrained into established practice that it can be hard to see why it’s problematic. A patriarchal ‘doctor knows best’ approach is still embedded in some clinical phrases, such as referring to ‘a non-compliant diabetic with poor glucose control.’

Wrapped up in that language is the idea that the patient is failing to comply with the doctor’s orders. As Diabetes Australia notes, it would be far better to talk about supporting a person with diabetes to manage their blood glucose levels within the target range. That language removes the negative judgement and instead emphasises personhood, partnership and agency.

What values are we trying to communicate?

As you can see, the language you choose expresses the values you hold. So, begin by identifying those. It’ll vary depending on your work and your clientele but might include values like being inclusive and supportive.

From there, you can begin to think about the language you use and whether it matches the values you’re trying to communicate.

The rich diversity of modern Australia

Australia is always changing. From the cities to the regions, from the coast to the bush, a wide variety of people call Australia home. We’re from different backgrounds, hold different beliefs, identify in different ways and live with different challenges.

Various statistics show:

- 78.6% of Australians have at least one long-term health condition

- Over 50% of Australians follow one of the major religions

- 46.6% have at least one chronic condition

- 30% of people living in Australia were born overseas and 23% speak a language other than English at home

- 4.4 million Australians (1 in 6) live with disability – and most of those disabilities are hidden ones like hearing loss

- 20% of Australians have a mental health condition

- 3.4% of adults identify as lesbian, gay or bisexual (based on aggregated studies)

- Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders make up 3.8% of the population

- Around 1.2% of Australian schoolchildren are thought to identify as transgender.

Best practice language examples

When you meet a person, you’re able to ask them how they’d like to be referred to. You can ask which pronouns they prefer or how they’d like you to talk about their health condition.

It’s trickier when you’re developing your website and other marketing materials because you need to choose a form of words and use those consistently. You may already have thought this through but, if not, we can help you brainstorm ideas and seek feedback from your clients or patients.

Here’s what’s considered best practice at the moment (though this is an evolving field and change is to be expected).

Person-first language or identity-first language?

Disability organisations emphasise the value of person-first language – ‘Don is a person with disability’ or ‘Laura is a person living with cerebral palsy’. This language recognises the person before mentioning the disability. Many disability organisations, governments and healthcare groups predominantly use person-first language.

As People with Disability Australia (PWDA) notes,

“People with disability are often described in ways that are disempowering, discriminatory, degrading and offensive. Negative words such as ‘victim’ or ‘sufferer’ reinforce stereotypes that people with disability are unhappy about our lives, wish we were ‘normal’, and should be viewed as objects of pity.

These harmful stereotypes are simply not true. People with disability are people first, who have families, who work, and who participate in our communities. People with disability want our lives to be respected and affirmed. In addition, many people with disability are proud of being disabled, and want that identity respected.”

However, as PWDA recognises, some people or groups prefer identity-first language – for example, ‘Miranda is autistic’ or ‘Louis is deaf’. Here, the person embraces their condition as part of their identity. This use is increasingly common among the Deaf community and neurodiverse communities.

Raising Children is a large Australian parenting website. They’ve chosen to use identity-first language and to refer to ‘autism’ rather than ‘autism spectrum disorder’. As they explain,

Many autistic people and autism experts and advocates prefer identity-first language because it indicates that being autistic is an inherent part of a person’s identity, not an addition to it.

Many people also feel that autism is a different way of seeing and interacting with the world, rather than an impairment or a negative thing. This difference is part of neurodiversity, which is the natural variation in how people’s brains work.

First Nations language

Given the diversity of nations, cultures and languages across Australia and the Torres Strait, there are very few hard and fast rules about how to refer to First Nations people.

The Australian government style guide recommends using:

- Specific terms (like a community’s name, island or nation) wherever possible – and consulting them about preferred terminology

- Broader terms only when truly referring to a large grouping (recognising that this involves homogenising groups with diverse cultures). Those broader terms might be:

- Regional terms such as ‘Murris’ or ‘Kooris’ if referring to many Torres Strait Islander peoples or islands

- First Nations people, First Australians or Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander peoples when referring to national issues.

It’s also important to use strengths-based language rather than deficit discourse. As the Lowitja Institute notes,

“There is evidence deficit discourse has real-world outcomes for identity formation, educational attainment, health and wellbeing. It contributes to forms of external and internalised racism.”

In contrast, a strengths-based approach recognises the capacities and capabilities of First Nations peoples. As Dietitians Australia explains,

“…there is a difference between a more deficit approach such as ‘helping disadvantaged Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people improve their nutrition’, and a more strengths-based alternative such as ‘strengthening Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples access to healthy foods’.”

Gender identity

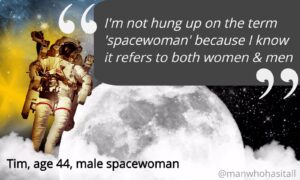

There are numerous English terms that use the masculine pronoun – mankind, manmade, manpower to name just a few. Find different ways of saying these such as humanity, hand-crafted or workforce.

Avoid using gender-specific job titles and pronouns in your copy. Recast job titles to focus on the role – chief executive, police officer, firefighter – rather than the gender of the person doing the job.

Where you need to refer to someone directly, it’s simpler to use the singular ‘they’. This is an inclusive term that captures people:

- Whose gender is unknown to you at this point (e.g. a potential job applicant)

- Who don’t wish to disclose their gender

- Who identify as non-binary or gender-fluid.

Similarly, instead of referring to ‘ladies and gentlemen’ or ‘guys and girls’ simply refer to ‘everyone’.

Sometimes the direct approach is the most helpful. Referring to ‘period products’ rather than ‘feminine hygiene products’ is both a more accurate description and more inclusive of transgender women.

Language evolves

Our society is forever changing – and so is our language. Redundant words are regularly pruned from our dictionaries while new ones are added to reflect the new situations we experience.

The ‘right’ terminology for your audience depends on the people involved. It’ll be a reflection of your practice, your patients and your community. This is an important part of your marketing – something we spend considerable time developing with you so that it is authentic and helps you connect with your intended audience.

You don’t need to have all the answers. What truly matters is a genuine commitment to continuous improvement and an openness to feedback from employees, customers, and stakeholders.

If you’d like to learn more, please book your free 30-minute consultation.

Sources

- Diabetes Australia, Our language matters: Improving communication with and about people with diabetes, http://diabetesaustralia.com.au/wp-content/uploads/Language-Matters-2021-Diabetes-Australia-Position-Statement-1.pdf, [Accessed 26 September 2023]

- People with Disability Australia, Language guide, https://pwd.org.au/resources/language-guide/, [Accessed 26 September 2023]

- Raising Children, Autism language on raisingchildren.net.au, https://raisingchildren.net.au/autism/learning-about-autism/about-autism/autism-language-on-raisingchildren.net.au, [Accessed 26 September 2023]

- Dietitians Australia, Guide to strengths-based Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communications, https://member.dietitiansaustralia.org.au/common/Uploaded%20files/DAA/Reconciliation/Guide-to-strengths-based-Aboriginal-and-Torres-Strait-Islander-communications.pdf, [Accessed 26 September 2023]